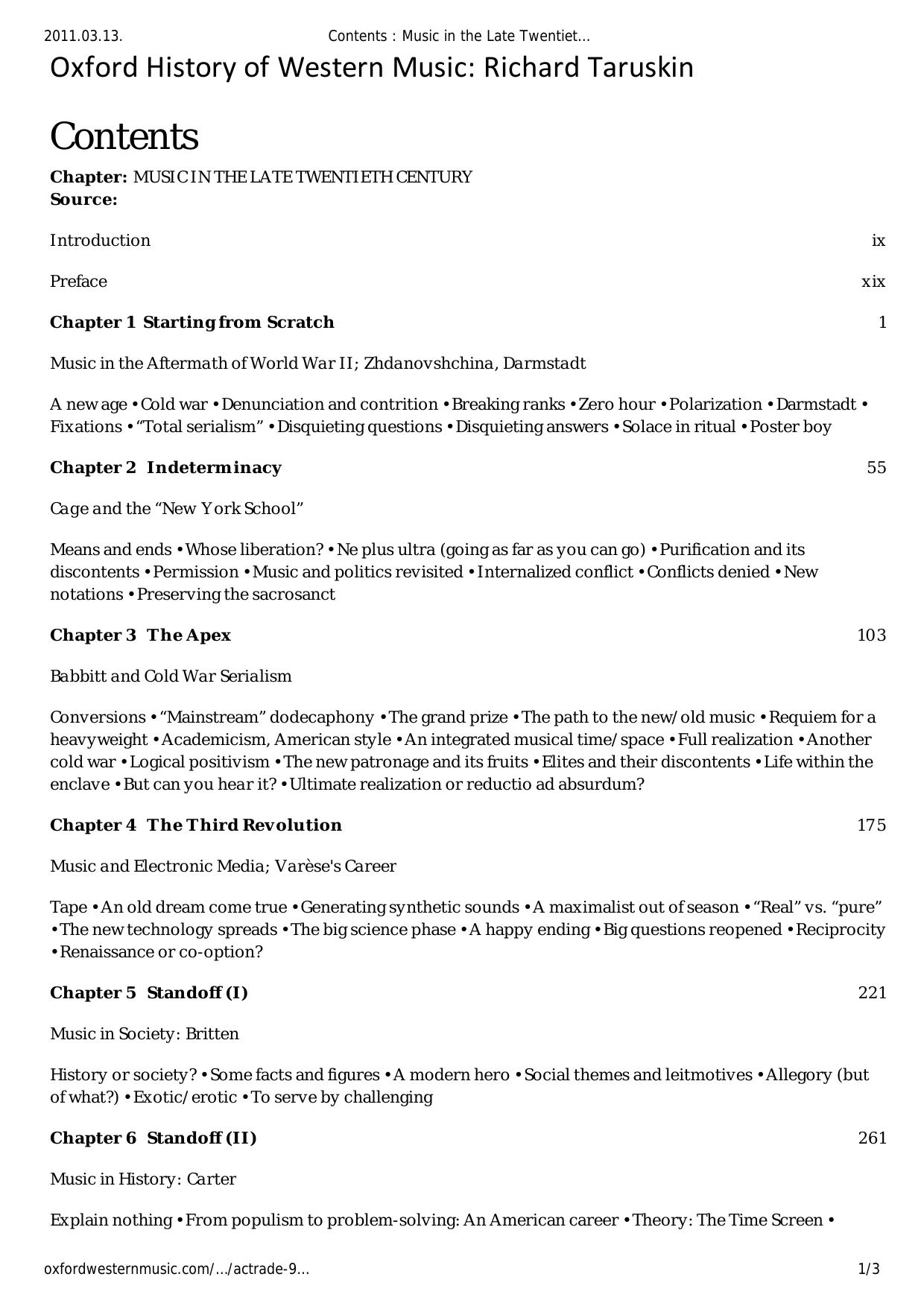

Music in the Late Twentieth Century by Richard Taruskin

Author:Richard Taruskin [Taruskin, Richard]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9780195384857

Publisher: OxfordUP

Published: 2007-09-15T05:00:00+00:00

Carter politely refused Boretzâs revision of his answer. By 1968 he could afford to break ranks, slightly, with the Princeton school without soiling his reputation as a serious artist on the most âuncompromisingâ terms. But there was no question of âpopulism.â His âextramusicalâ reference was, in the first place, not to the fairly raw experience of life, still less to the sort of social problems Britten addressed in Peter Grimes, but to fairly esoteric classical and neoclassical literature. And the âextramusicalâ content, such as it was, was on a cosmic plane infinitely removed from that of human tribulation and emotion (save that of wonder).

Carter remained for the rest of the century the chief standard bearer of autonomous musical art, and a bulwark against the âpostmodernistâ tendencies that began to emerge, and threaten the modernist faith, in the 1980s. His reputation gathered ever greater luster after the turn of the century as he continued, astoundingly, to compose with undiminished vigor up to and beyond his own centennial anniversaryâan absolutely unprecedented feat of creative longevity that made him, finally, a genuine media sensation. Some evidence of ambivalence can be found, beginning in the eighties, in Carterâs writings. He has occasionally argued, apparently against the conventional wisdom, that for all its surface complications and its formidable intellectual rigor, his music has always been at bottom an expressionâmore properly, a representationâof American ideals. âA preoccupation with giving each member of the performing group its own musical identity characterizes my String Quartet No. 4,â Carter noted in the preface to that work, published in 1986, âthus mirroring the democratic attitude in which each member of a society maintains his or her own identity while cooperating in a common effortâa concept that dominates all my recent work.â

That message, however sincerely meant, has nevertheless been mediated through a discourse of elitism. In Clement Greenbergâs terms, Carter has been, preeminently, the late twentieth centuryâs âmusiciansâ musician.â His visions of democracy have been of interest primarily to a coterie of professionals: fellow composers, performers, scholars, and academically inclined or affiliated critics, for whom Carterâs music has often served as a touchstone of self-congratulation. But the ambiguities of Carterâs position were always implicit in the way his music has been promoted, ever since he won his European recognition as a protégé of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, clandestinely funded by the CIA in defiance of the egalitarian (or at least anti-intellectual) biases of the United States Congress, which would have opposed the use of tax revenues to support élite culture on the European model. Carter thus became one of the protagonists of that âsublime paradox of American strategy in the cultural Cold War,â defined by Frances Stonor Saunders, whereby âin order to promote an acceptance of art produced in (and vaunted as the expression of) democracy, the democratic process itself had to be circumvented.â54

Carterâs champions have been particularly vocal in defending asocial theories of music history. Especially prominent among them has been Charles Rosen, already mentioned as the pianist in

Download

Music in the Late Twentieth Century by Richard Taruskin.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Biographies | Business |

| History & Criticism | Instruments |

| Musical Genres | Recording & Sound |

| Reference | Songbooks |

| Theory, Composition & Performance |

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13651)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11810)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7557)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6197)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6194)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5790)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5092)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4995)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3603)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3542)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3298)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3296)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3257)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3139)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3071)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3057)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2978)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2856)